Moore Group was engaged by Galway City Council as the consulting archaeologists for the Eyre Square Re-enhancement Project and from the outset in February 2004 carried out archaeological testing and monitoring of groundworks. A number of excavations were carried out during the scheme. Some post-excavation is ongoing and a final report will be prepared soon. Over the coming months we’ll post some snippets from the excavations here. We’ll start at the top (north end) of the Square and the discovery of an 18th century building.

18th Century building (market house) at north end of Eyre Square

An excavation, directed by Billy Quinn, was carried out to the north of Eyre Square in an area previously utilised as a taxi rank and carriageway (for those of you familiar with the city – that’s in front of the Bank of Ireland). Previous archaeological testing within this area had exposed structural remains indicating the presence of an 18th Century building. Although it was feasible to preserve the building in situ, with the agreement of the DEHLG and the support of Galway City Council, a small part of the area was excavated -the excavation incorporated areas both inside and outside the wall footings to provide meaningful data. Despite the fact that the building could have been left untouched, the City Council agreed that this was a great opportunity to investigate a previously unknown feature prior to sealing it up in perpetuity.

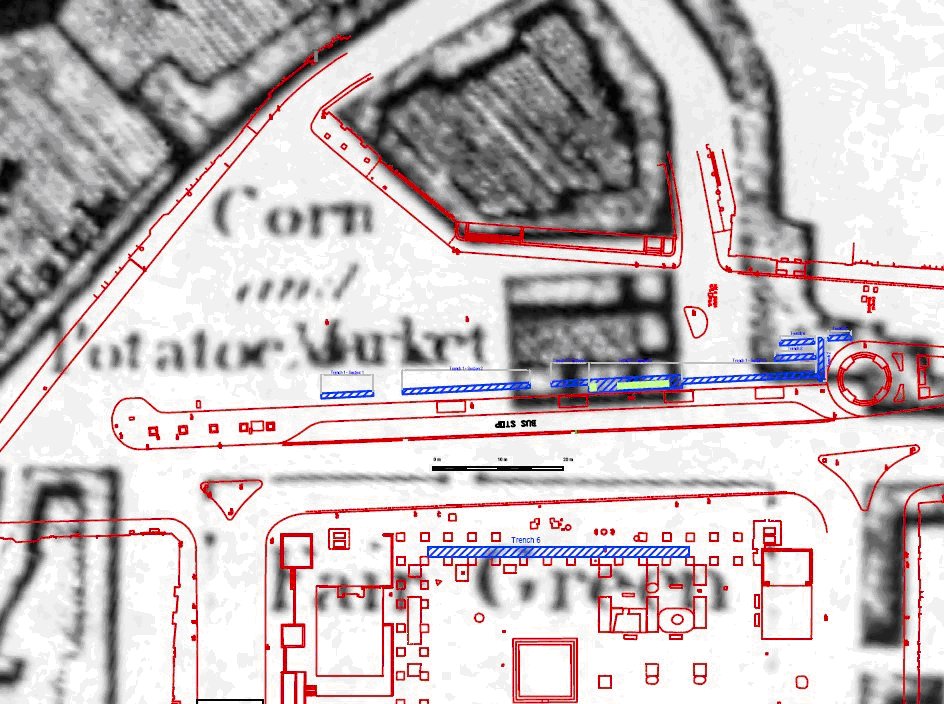

Logan’s map reproduced above depicts the square as a park area indicated both as the ‘Fair Green’ and ‘Mayrick’s Square’. To the north east of the square is an open space known as the potato and corn market. West of this is a square development block with approximately six structures enclosing a yard that corresponds with the square block on the Erasmus Smith 1785 map. This block is located in the area of the present day taxi rank and bus terminal and is most likely related to the wall foundations exposed during the excavation. On the later 1839, 1st Edition OS sheet this block does not appear, presumably having been demolished to enlarge the market space. We’ve reproduced below an extract from Logans map overlaid with the present day site plan showing the structural foundations exposed during excavation in relation to the block described above. The foundations we excavated generally correspond to this long since demolished building.

Prior to the manual excavation a large area to the north of the present day bus rank was machine excavated to an average depth of 0.4m, removing the tarmac, hardcore and underlying mixed gravel layers. This bulk reduction work was essentially carried out to determine the extent of the structural remains previously recorded in the testing phase and to define the limit of excavation. On completion of the stripping operation the exposed open area was roughly ‘L’ shaped in plan with the longer axis orientated NE/SW measuring 21m by 6m and the shorter axis orientated NNW/SSE measuring 10m in width by 10.5m in length. This area was enlarged at a later date to the south, west and northwest. The southern extension was opened to re-expose the south wall; the west and north west extension’s were designed to investigate a possible return on the west wall and to examine a stone lined pit that later transpired to be a latrine with associated drain.

The plate reproduced below, taken from the roof of the nearby Bank of Ireland (who kindly allowed us access), is an aerial view looking south to the site. The plate shows very generally the main archaeological features comprising the foundations of a rectangular building, a circular ash Pit and the stone lined latrine. The slot trench located in order to investigate the stratigraphy inside and outside the wall is evident on either side of the ranging rod.

The earliest deposit exposed during the course of the excavation was the first of three metalled surfaces found within one of several investigative slot trenches. This was a roughly laid metalled surface of sub-rounded, poorly sorted, cobble sized, limestone within a silty peat matrix and measured approximately 0.75m N/S by 1m E/W. Sealing this surface was a softly compact, mid brown, sandy silt, organic layer with inclusions of burnt and un-burnt animal bone, oyster, periwinkle and mussel shell, brushwood and a single gold plated copper pin. Overlying that was a midden-like deposit, varying in thickness from 4cm to 11cm. The only significant find recovered from this layer was a gold plated round headed pin similar to the example found in the deeper layer described above.

Above all that there was another rough cobble layer. From the cartographic record there is evidence for a roadway in the vicinity of the site from the mid 17th Century. This cobbled surface probably represents the final phase of roadway activity prior to the site being re-used, initially as an open market, evidenced by the accumulation of organic refuse (described below), and later for the site of the Market house.

A composite layer consisting of moderately compact, brown clay with frequent inclusions of stone, animal bone and oyster shell was above the 17th century roadway. This layer measured on average 0.2m in depth and contained an assortment of post-medieval finds including pottery, glass, clay pipe, tile sherds, worked shoe leather and two gold plated pins.

The structural remains exposed during the testing phase and the initial mechanical excavation work uncovered a roughly rectangular structure measuring approximately 12m E/W by 6.35m N/S. This rectangular block was open ended to the east with no evidence for a return and was later truncated by a modern service trench orientated NNE/SSW. It was apparent that the building was constructed in two phases, built, partially demolished leaving the southern and western walls intact and rebuilt and enlarged at a later stage. The masonry was bonded with a mid to dark brown coarse sand lime mortar.

Among the other features exposed during the course of the excavation in Areas B and C to the north of the rectangular structure were a circular ash pit, a latrine, and associated drain.

The Latrine

The Latrine, found to the north of the north east corner of the rectangular structure in Area D was initially exposed as a ‘U’ shaped arrangement of stone with an associated drain in the form of a linear stone alignment. Subsequent excavation of the feature revealed a stone lined, rectangular pit with a backfilled drain running to the north. The internal pit dimensions measured 1.03m N/S by 0.5m E/W and had a maximum depth of 0.51m. The stone revetment was constructed of randomly coursed, roughly hewn limestone with smaller spall stones. There was no evidence of any bonding agent. The pit, as is obvious from the photograph, is open to the east – whether this was deliberate or the result of later demolition is unclear. An investigation around the feature to determine the original cut-line exposed a sub-circular fill extending to the west beyond the limits of the extant revetment; this would seem to indicate that the pit was originally enclosed. The fill within the pit was a friable, dark brown silty sand with frequent inclusions of pottery, bone, wood and stones. A worked piece of timber retrieved from the pit had a deliberate hole cut in its mid section and probably functioned as the toilet seat. The entire timber was retrieved and has been conserved.

To the NE of the latrine and running N to the edge of excavation was a drain feature that measured 0.95m in length by 0.5m in width.

We concluded that the remains of the eighteenth century rectangular building were possibly related to the block of buildings marked on Logan’s 1818 map to the east of the old Corn and Potato market. The building probably functioned as the original market house which was subsequently moved to the present day site of the Bank of Ireland. Two distinct building phases were evident suggesting that the original building was partially demolished and enlarged – possibly in the early nineteenth century. By the time of the 1st Edition OS map in 1839 this building had been totally demolished allowing for an extension of the open-air market to the east.

Contemporaneous with this general phase was a latrine and ash pit. Neither of these features appeared to have associated enclosing elements. However it is very unlikely that they were exposed to the elements and were probably sheltered by a timber structure.

Underlying the market house were a series of archaeologically significant organic deposits containing a wide variety of finds including medieval to post medieval pottery and tile, worked leather shoes and offcuts, three gold plated pins, fragments of early clay pipes, an amber bead and a pre-historic flint. Three successive metalled surfaces were also exposed consisting of compacted cobbled sized sub angular stone. These surfaces mark the original roadway as featured on Bellin’s 1786 map leading eastward from the walled town towards Prospect Hill.

Unfortunately due to time constraints brought about by adverse weather the site was not bottomed out to natural levels, however excavation did expose extant archaeological levels at a depth of 1.7m below the existing road level. The preservation in situ of these deposits was made possible by the cooperation of the landscape architects and contractors in raising their finished structural levels to avoid any direct impacts. On the completion of the excavation the entire site was covered with geo-fabric and backfilled with gravel.