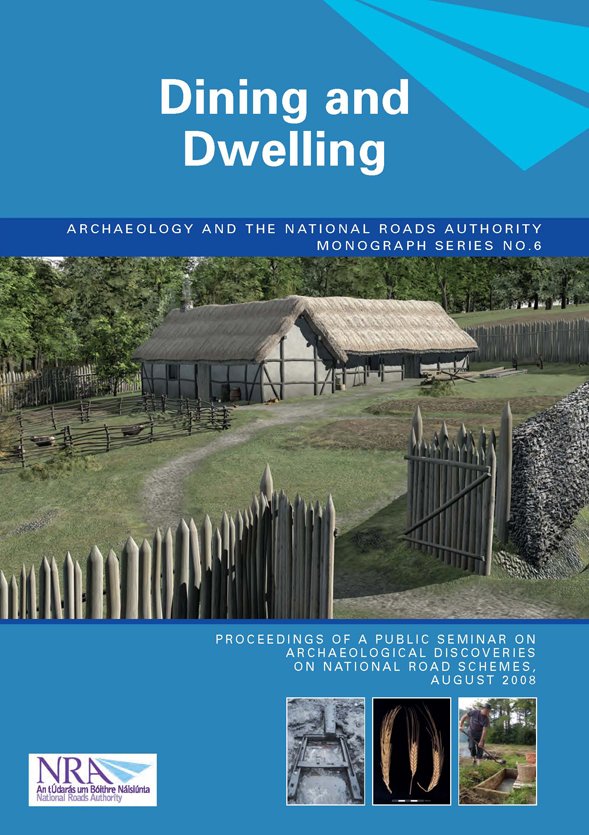

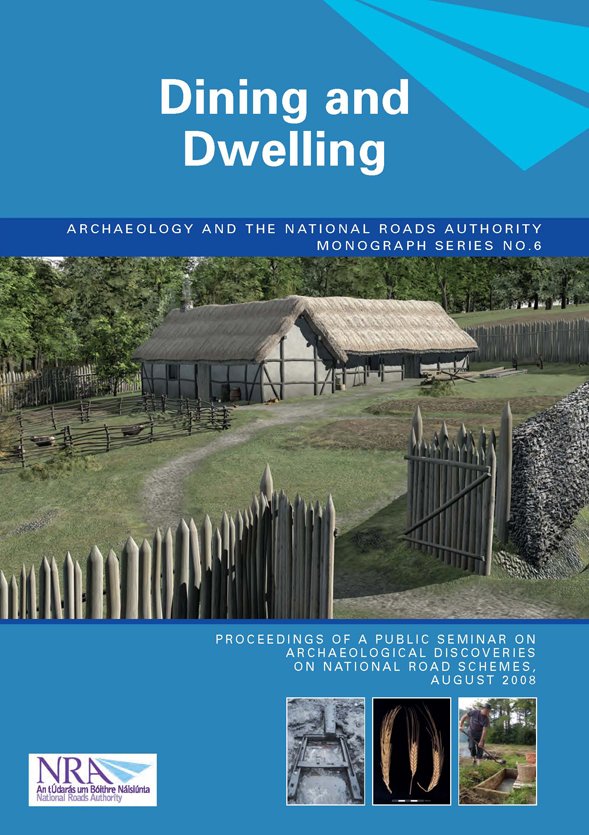

Dining & Dwelling

Last year Billy and Declan gave a presentation at the National Roads Authority’s annual archaeology seminar about the fulacht beer theory. You can see a video of the presentation here. The resultant monograph Dining and Dwelling has just been published by the NRA and is available through bookshops or directly from Wordwell Book Sales, Wordwell Limited, Media House, South County Business Park, Leopardstown, Dublin 18 (tel: +353 1 2947860; email: helen@wordwellbooks.com).

The publishers have kindly permited us to republish our piece here. We’ll post it in parts over the coming week or so as it’s quite big. For those who’ve been reading about the beer there’s some stuff you’ve already heard about but we have added a lot more background and detail. So here’s part one:

FULACHTA FIADH AND THE BEER EXPERIMENT

Billy Quinnand Declan Moore

Fulachta fiadh, or burnt mounds, generally date from the Bronze Age and are one of the most widespread of Irish field monuments, perhaps numbering up to 5,000. Of the 500 or so sites currently entered in the NRA Archaeological Database (http://www.nra.ie/Archaeology/NRAArchaeologicalDatabase/ last accessed 20 August 2008), 28% are fulachta fiadh (with associated features) or burnt mounds/spreads (no associated features). To date, they have been excavated on road schemes in 18 counties, in all provinces. Typically, a fulacht fiadh site is defined by a low, horseshoe-shaped mound. Upon excavation the mound consists of charcoal-enriched soil and heat-shattered stone around a central trough.

The name derives from Geoffrey Keating’s 17th-century manuscript Foras Feasa ar Éirinn and as a complete term does not appear in any early manuscripts (Ó Néill, 2004). Conventional wisdom, based largely on Professor M J O’Kelly’s 1952 experiments in Ballyvourney, Co. Cork, suggests that they were used for cooking (ibid.; O’Kelly 1954). Alternative theories that have been proposed include bathing, dyeing, fulling and tanning. It is, however, generally agreed that their primary function was to heat water by depositing fired stones into a water-filled trough. In this paper we would like to explore a further hypothesis, reported previously elsewhere (Quinn & Moore 2007); namely, were some fulachta fiadh prehistoric micro-breweries?

SO WHERE DOES BEER COME INTO IT?

In order to answer this we have to look into the natural history and archaeology of intoxication. The inebriation of animals has been documented anecdotally (Dudley 2004), but has received little scientific attention. There is evidence from around the world of animals experiencing drunkenness as a result of consuming overripe fruit containing yeast (producing ethanol) resulting, unsurprisingly, in inebriation.

Indeed, what may have been drunken behaviour by Howler Monkey’s in Panama’s Barro Colorado Island was observed by Dustin Stephens, leading Stephens and Robert Dudley of the University of California, Berkeley, to the preliminary conclusion that ‘preference for and excessive consumption of alcohol by modern humans might accordingly result from pre-existing sensory biases associating ethanol with nutritional reward’ (Dudley & Stephens 2004, 318). Put simply, the so-called Drunken Monkey Hypothesissuggests that natural selection favoured primates with a heightened sense of smell for psychoactive ethanol, indicative of ripe fruit, who would thus have been more successful in obtaining nutritious fruit!

Early hunter-gatherers had an intimate knowledge of the environment around them and the effects of naturally occurring intoxicants, but the discovery of fermentation may simply have been a happy accident involving overripe fruit. However, as agriculture took root, barley and wheat became plentiful, which in turn provided good substrates for beer or ale.

There’s no argument that people were drinking beer throughout the world in prehistory. As Pete Brown says in Man Walks into a Pub (2003), ‘even elephants eat fermenting berries deliberately to get p*****d and we are much more cleverer than them [sic]’.

Recent chemical analyses of residues in pottery jars from a Neolithic village in Northern China revealed evidence of a mixed fermented beverage from as early as 9,000 years ago (McGovern et al, 2004). Clear chemical evidence for brewing in Sumeria at Godin Tepe (in modern day Iran) comes from fermentation vessels where there were pits in the ground noted by the excavators (Michel et al, 1992). In the Hymn to Ninkasi (Civil, 1964) by a Sumerian poet (dated1800 BC) and found written on a clay tablet is one of the most ancient recipes for brewing beer using pits in the ground:

‘You are the one who handles the dough,

[and] with a big shovel,

Mixing in a pit, the bappir with sweet aromatics’

In north-western Europe there is evidence of Neolithic brewing at Balbirnie in Scotland and at Machrie Moor, Arran where organic residue impregnated in sherds of Grooved Ware pottery were described as ‘perhaps the residues of either mead or ale’ (Hornsey,2003, 194). . Based on the highly decorated, beaker-shaped pottery vessels characteristic of the Bronze Age Beaker Culture it has even been suggested that Beaker people traded in some sort of alcoholic beverage and that the beakers may have been high-status drinking vessels.

Regarding Ireland, the first known reference to beer is in 1 AD (Griffiths 2007, 11), when Dioscorides (a Greek Medical writer) refers to ‘kourmi’ (a plain beer, probably made from barley) although Max Nelson relates this as a reference to Britain (Nelson 2005, 51, 64). Much later, Saint Patrick appears with ‘the priest Mescan . . . his friend and his brewer’. Perhaps unsurprisingly Patrick considers his friend and brewer to be ‘without evil’ (Annal M448.2).

As Zythophile points out in his post ‘St. Brigid and the Bathwater’ in the blog ‘Zythophile’, ale was an important part of Irish society. He notes that the Crith-Gablach (a 7th Century legal poem), for example, declared that the ‘seven occupations in the law of a king’ were:

‘Sunday, at ale drinking, for he is not a lawful flaith [lord] who does not distribute ale every Sunday; Monday, at legislation, for the government of the tribe; Tuesday, at fidchell [a popular early medieval board game]; Wednesday, seeing greyhounds coursing; Thursday, at the pleasures of love; Friday, at horse-racing; Saturday, at judgment.’

Sundays and Tuesdays must have been particularly taxing.

The following jumped out and we were surprised we hadn’t noticed it:

‘A record of a fire at the monastry of Clonard … around AD787 speaks of grain stored in ballenio, literally ‘in a bath’, which seems to mean the grain being soaked as part of the initial processes of malting.’

Zythophile suggests that what St Brigid drew off may have been water from the ballenium where the grain was steeping in the first stage of malt-making.

NEXT POST: THE GREAT MYSTERY OF PREHISTORIC BREWING

This entry was posted on Monday, September 14th, 2009 at 1:26 pm. It is filed under About Archaeology, About the Beer, Fulacht fiadh and tagged with ancient beer, Dining and dwelling, Fulacht fiadh, National Roads Authority, NRA.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.