19th Century Burial in Ireland – Part III

Part III of our paper in the JIA.

St Brigid’s Hospital, Ballinasloe

A second excavation of 19th Century burials was carried out within the grounds of St Brigid’s Hospital, Ballinasloe, County Galway in August 2002. Part of the grounds had been acquired by Galway County Council for the construction of a slip road and burials were uncovered during archaeological testing ahead of the road improvement.

Twelve graves were excavated under the direction of Declan Moore. These are described in more detail below. No direct evidence of the date of these inhumations was recovered, although 19th or early 20th century pottery and other small finds within the grave fills indicated that they were buried in this period and it is reasonable to conclude that the burials are associated with the Hospital which was formerly the Connaught Asylum.

Medieval or early post-medieval burials were also identified during archaeological testing slightly to the east of the proposed slip road but these were not excavated. These graves were of a different character, state of preservation and orientation to the twelve excavated burials and are attributed to nearby Creagh church. This ruined church now stands within an extensive burial ground to the south of the hospital grounds, on the opposite side of the public road. It appears from the results of archaeological test excavations, however, that this ancient burial ground once extended into the area now occupied by the precinct of St Brigid’s Hospital.

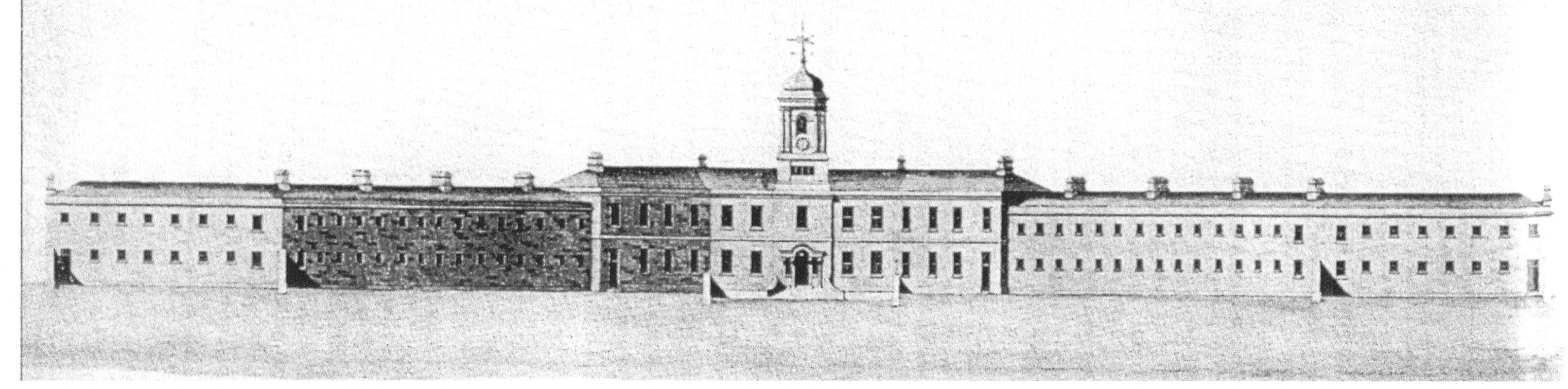

Front elevation of St Brigids hospital Ballinasloe

The provision of Public Asylums

Legislation for the mandatory provision of public asylums was adopted in Ireland with the Irish Lunatic Asylums for the Poor Act of 1817. In 1804 a House of Commons select committee had recommended the provision of four provincial asylums in Ireland, including one in Dublin, each to have 250 beds (O’Dwyer 1995). Such legislation was the first of its kind and was followed by France and Switzerland only in 1838, and by England in 1845. In his excellent study on the development of the Public Asylum in Ireland, Reuber (1995) describes the adoption of the ‘panoptic’ design which was used at Ballinasloe. The following information is based on that study.

The first public institution to be built solely for the reception of lunatics was the Richmond Asylum in Dublin. It was built between 1810-15 to a design by Francis Johnston from Armagh, the architect to the Board of Works. The design, which was quadrangular, enclosed a courtyard, but proved unsatisfactory, penitential and unsuitable for expansion, and new ways were explored for the improvement of hospital architecture. The 1817 legislation resulted in the construction of nine institutions and the extension of the Richmond Asylum. Design was again provided by Johnston and his assistant, Francis Murray. Their new plans were influenced by the ‘panoptic’ prison concept, first advocated by the economist Jeremy Bentham, and they had already used this in their design of the Richmond Penitentiary, built 1812-18. The principle behind this was to allow a governor, his family and turnkeys to occupy a central structure, with radiating wings from which they could monitor and administrate life within the institute. The arrangement allowed the wings to be viewed from the centre, while access was only possible from one wing to the other by passing through the centre. Plans were submitted for two sizes of institute 100 and 150 beds. Johnston’s designs were ultimately only adopted for the larger, Class I Asylums, of which only two were built, the first in Limerick and the second in Ballinasloe. They were fronted in classical style with a two-storied centrepiece topped by a cupola and flanked by ward blocks.

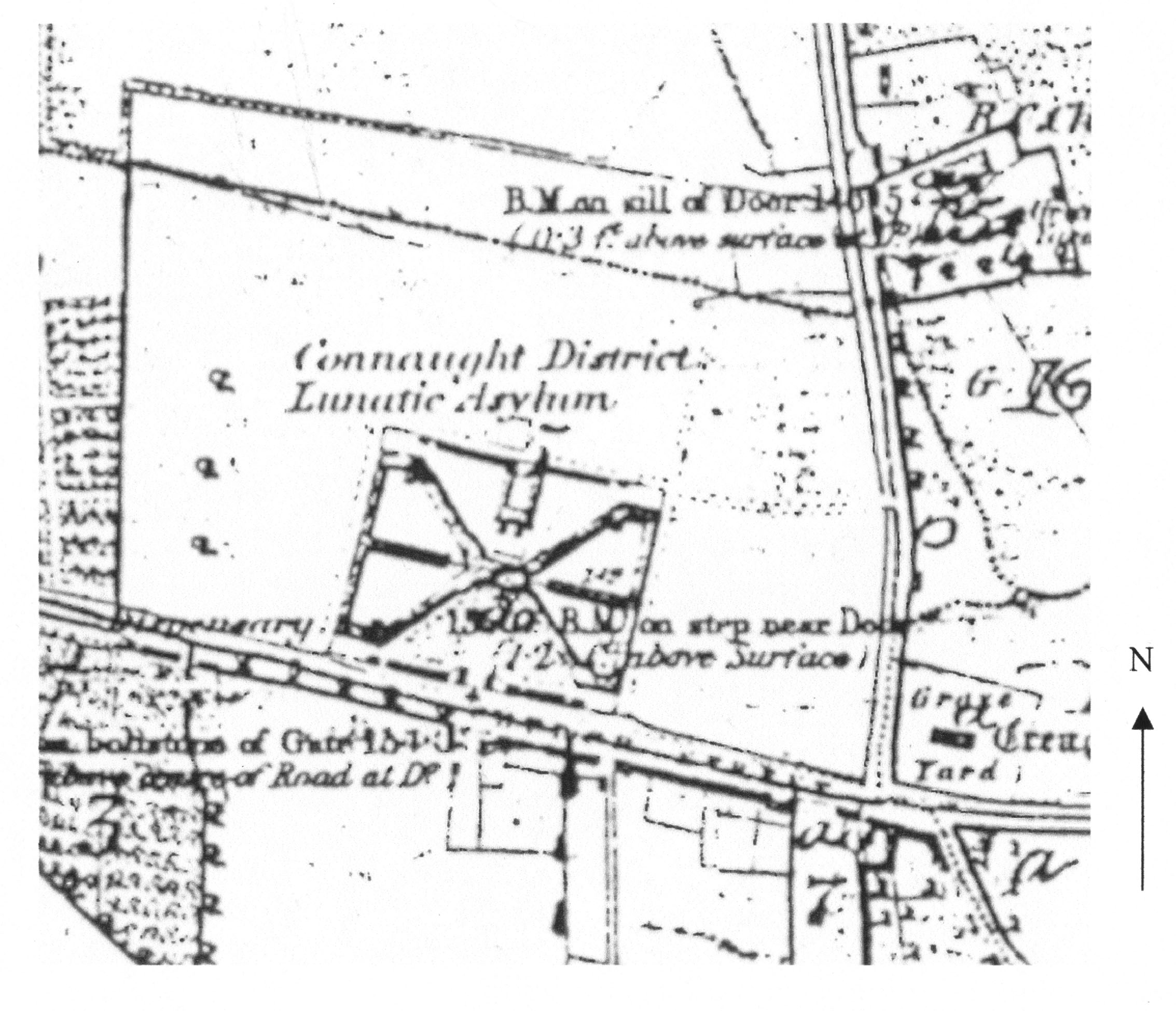

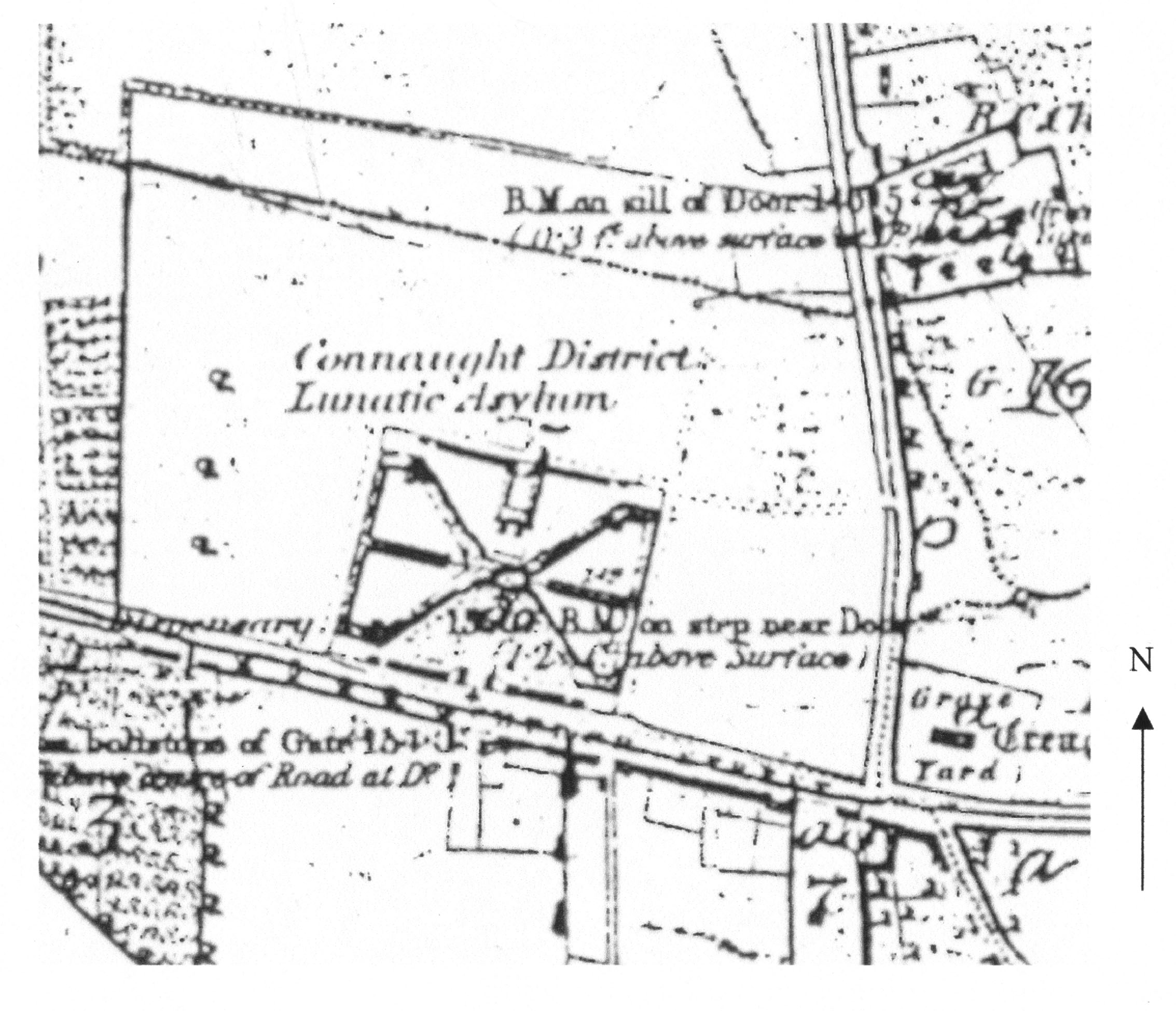

Extract from 1837 ordnance survey map

The Connaught Asylum

St Brigid’s Mental Hospital was opened as the Connaught Asylum in 1833 with accommodation for 150 patients. The date is inscribed above the door in Roman numerals. The building is shown on the first edition Ordnance Survey map, surveyed in 1837. The cost of building was £27,000. It remained the Connaught Asylum until 1850, when the Sligo Asylum was built to cater for the counties of Sligo and Leitrim, and it was then renamed Ballinasloe District Asylum, to serve the counties of Galway and Roscommon only. New wings were added in 1871 and 1882 but by 1896 the number of patients had risen to 935 and a new detached block on the eastern side of the complex (beside the excavated archaeological site) was begun. It was first occupied in 1901 when the number of patients had risen to 1004. In 1924 a former college, known as The Pines, was acquired and there were further new buildings erected in the 1930s, when the Admission Hospital on the Athleague Road and additional annexes, St Joseph’s and St Enda’s, were all added. The name of the hospital was changed to St Brigid’s in July 1960 (Mac Lochlainn, 1971, 77). The Asylum is listed in the Galway County Development Plan as a protected structure, under the Local Government (planning and development) Acts 1963-2000.

Although there is little historical evidence concerning the burial ground discovered within the south-east corner of the hospital grounds, a map held by the hospital authorities shows an area marked as ‘old burial ground’. The map is undated but shows dateable evidence. The original layout of Johnston and Murray’s plan was a simple X pattern built in the panoptic design as described above. However, the map shows two additional wings on either side, one shaded and one outlined. Mac Lochlainn (1971, 79) records that a wing was added to the men’s side of the hospital in 1871 and another to the women’s side in 1882. As the map seems to show one wing finished and one in the process of being built this dates the map to some time in the 1880s. The burial ground is marked ‘old burial ground’ which suggests that it had gone out of use by this time.

Archaeological excavation results

During initial construction works for the new slip road in 2001, human skeletal remains were uncovered. A total of 71 grave cuts were observed in archaeological test trenches and a further 21 possible inhumations were evident on site or in the section faces of trenches already dug (Moore and Rogers 2002). Galway County Council redesigned the proposed development to avoid these burials and work on the road was resumed.

During construction works associated with the road in August 2002, a number of further graves and inhumations were exposed. These lay to the west of the area previously tested and where the main concentration of graves had been observed. Following discussion with Galway County Council and the Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, and given the advanced stage of construction works, full excavation of a strip at the east side of the proposed road was undertaken to record and remove these burials. Although only twelve of the burials were fully excavated, it is clear that the graves formed part of two regular, north-south rows. Only one phase of burials was apparent. The layout of the graveyard concurs with the findings from test trenches previously opened in the south-eastern part of the hospital grounds, where several distinct rows of graves were distinguished. In contrast, trenches opened at the very east, closest to the boundary wall, revealed cross cutting graves at different levels, implying that more than one phase was present. The reasons for this different presentation in two areas will be discussed below but, for the moment, it can at least be said that the graves represent two different periods of burial in this area.

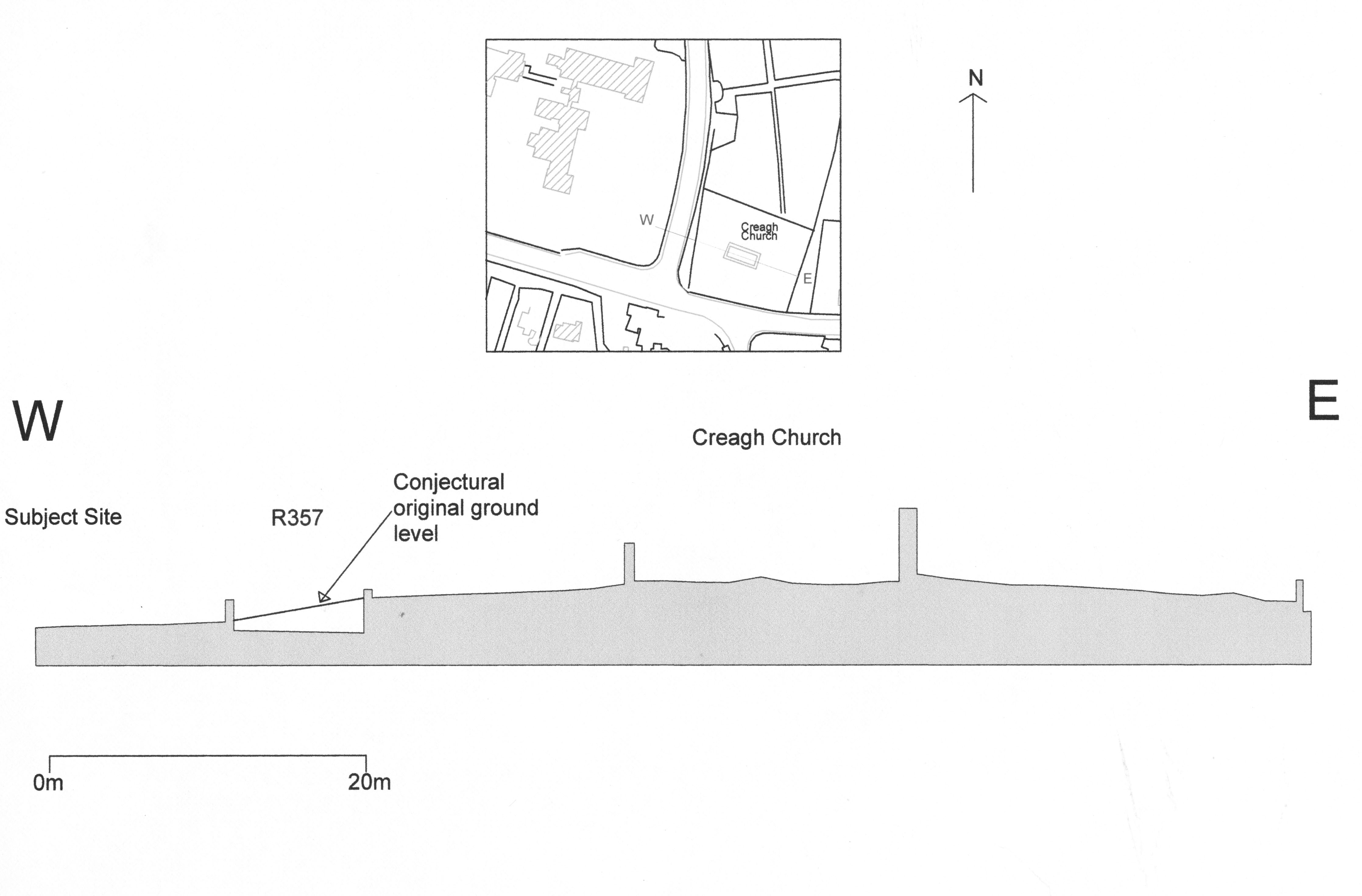

Creagh junction site viewed from the south

All of the grave cuts excavated were roughly rectangular in plan and were generally filled by a loose, mid-brown, sandy silt with occasional rounded stones. Despite the generally good bone preservation, little was found of the coffin wood, reflecting the generally dry conditions across the site. Nails were found in abundance but no fixtures, fittings, plates or handles were uncovered, all evidence pointing to simple, Christian burials. Those timbers recovered were identified as spruce, sawn diagonally from fast-grown wood (Stuijts, 2003). It is very likely that the samples examined came from managed woodland, considering their fast growth rate. Spruce was introduced into Ireland in the 1700s and its use as a coffin material supports the interpretation of a post-medieval date for this part of the site.

Skeletal remains

The skeletal remains were examined by Linda Fibiger (Fibiger 2002). Preservation was generally very good with most joint surfaces intact and a minimal degree of fragmentation – a result of a favourable burial environment. The majority of skeletons were virtually complete and only a small percentage of the small bones of the hands and feet were missing. Only burial 11, which had been truncated by a mechanical digger at knee level, was poorly preserved. All were supine and extended, with arms by their sides.

Burial 3 creagh junction

Of the twelve skeletons eight were mature adults (45+ years) and the remaining four were old adults (36-45 years). Seven were male, three were female and the remaining three are likely to have been female. The mean stature, based on the length of long-bones, was 169.3 cm (5′ 6″) for the males and 155.7 cm (5′ 1″) for the females. The majority of individuals present survived into old age, probably even into their sixties or longer (as indicated by the presence of progressively ossified thyroid cartilage). This allowed for the development of advanced degenerative changes to the joints and severe dental disease. The presence of os acromiale, lumbar spondylolysis, osteochondritis dissecans and a variety of enthesopathies and cortical defects indicate a certain level of physical activity for most individuals present, suggesting either that they worked within the institution or they had worked previous to entering the institution. Apart from skeleton 5, all showed signs of osteoarthritis or joint deterioration and, in addition, skeleton 8 had rheumatoid arthritis. Several of the skeletons had fractures and skeleton 12 had a fracture of the zygomatic arch (cheek bone), which suggests a blow from a right-handed person. Also present was a case of bilateral spondylolysis affecting the fifth lumbar vertebra of skeleton 12, which suggests strenuous activity during life. Skeleton 5 had ‘wry neck’, a condition which is characterised by sideways tilting and rotation of the head (lateral flexion) due to muscular shortening. The prevalence of dental pathologies suggests two things: poor dental hygiene and a sucrose-rich diet. Those who had lost most or all teeth during life must have been catered for with a special soft diet, taking into consideration their lack of ability to chew.

The origin of the burials

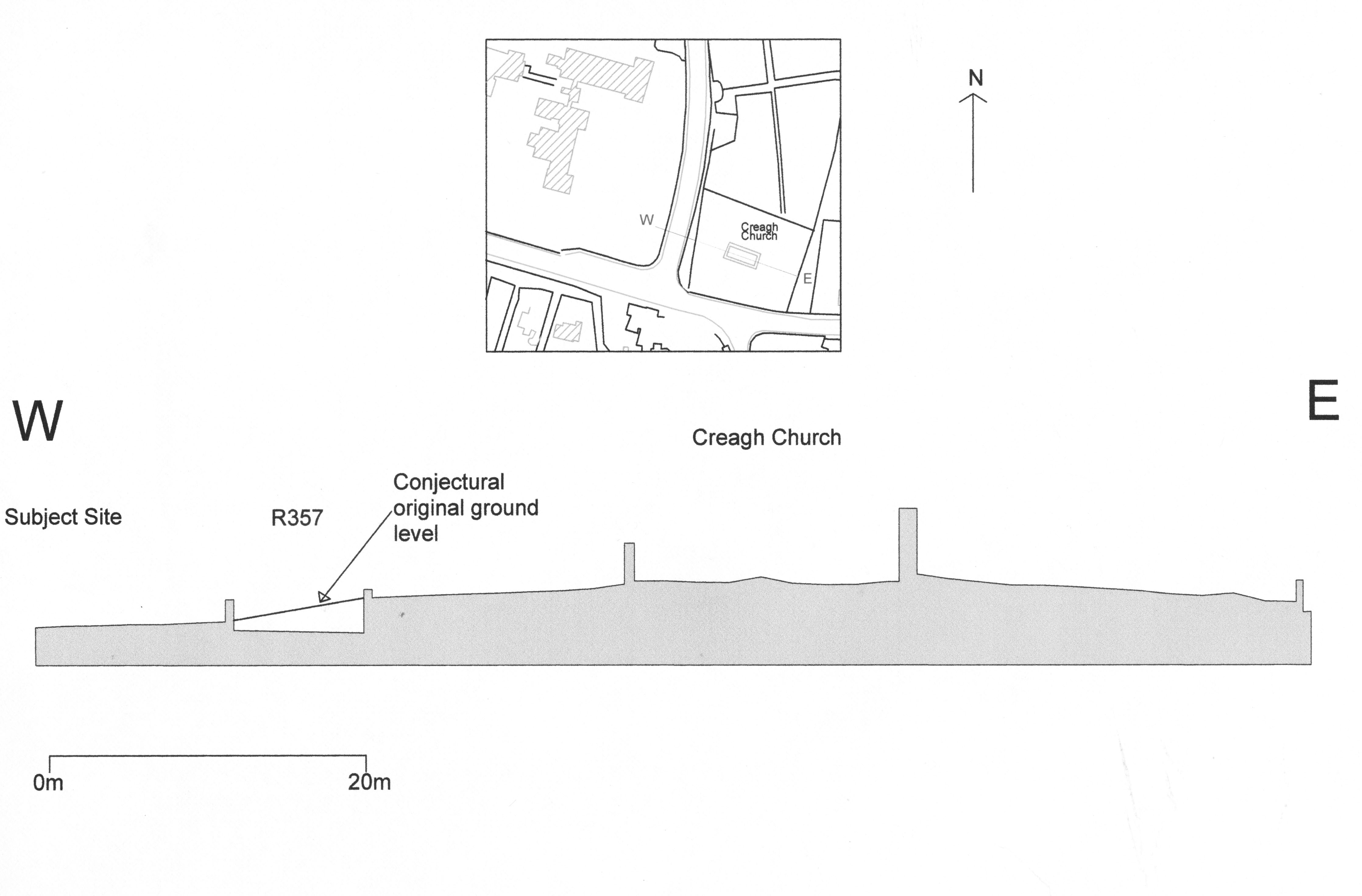

The presence of inhumations at this site within the hospital grounds was locally known and it has been suggested that burials were uncovered in the last century during roadworks on the same road junction. The final figure below shows the results of a profile survey across the hospital grounds, road and church and a postulated former ground level. The present church ruin on the opposite side of the Creagh/Athleague Road is probably no older than the 18th century (Egan 1960, 27). However, the survey makes clear that it is built on a small rise or mound which itself is likely to be older still. It can be deduced that the Athleague road, which divides the hospital grounds from the churchyard, was a road improvement which cut the western edge of this mound, isolating a strip of the former churchyard on the west of the road, which was later became part of the hospital grounds. This argument is supported by map evidence from the Ordnance Survey of 1837 as well as by Taylor & Skinner’s (1777) more rudimentary road map for this area.

Profile across creagh churchyard and eastern edge

In all, it is clear that some of the burials found within the 19th-century asylum boundary walls may be associated with much earlier activity associated with Creagh church. If burials were known to exist at this corner of the hospital grounds, it would have been an obvious step to continue its use as a burial ground for inmates of the asylum and, over time, to continue to expand the graveyard to the west. The twelve burials described here appear to be of this later phase. White glazed and decorated 19th or early 20th century ceramic sherds were found in several of the burial fills, but there is no material evidence to date the graves more accurately.

This entry was posted on Wednesday, October 22nd, 2008 at 11:13 am. It is filed under About Archaeology, Papers & Reports and tagged with archaeological consultants, Archaeological excavation, ballinasloe, Co. Galway, Creagh Junction.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Where was this asylum located do you know? – http://irishurbanexplorations.wordpress.com/2013/11/04/the-abandoned-asylum-march-2013/

It doesn’t appear to be the Ballinasloe/Limerick one.

Look like Ballinasloe.

See this view from Google Maps – the red container is the same.

https://maps.google.ie/maps?q=ballinasloe&hl=en&ll=53.329749,-8.202968&spn=0.002659,0.006968&sll=53.3834,-8.21775&sspn=10.890863,28.54248&t=h&hnear=Ballinasloe,+County+Galway&z=18&layer=c&cbll=53.329843,-8.20291&panoid=s8PaYMd0QudhG5FLP4EWKQ&cbp=12,276.71,,0,9.77

it is Ballinasloe as i live near there