19th Century Burial in Ireland – Part II

Part II – Manorhamilton Workhouse (see part I for authors and introduction, here for Part III, the Connaught Asylum in Ballinasloe and part IV for the conclusion and bibliography).

Background to Manorhamilton Workhouse

Despite a considerable slowing of the growth rate after 1820, the population of Ireland trebled in the century preceding the famine (O’Grada 1989, 5). Leitrim suffered, as did the rest of Ireland, from the combination of a rapidly growing population and a system in which one third of the landholders farmed two thirds of the land (O’ Grada 1989, 22). It is estimated that at the end of the 18th century two million people were at starvation level. As a response, the British Government appointed a Select Committee in 1804 and a Royal Commission in 1825. Although the Commission recommended some wide-ranging solutions, including the reclamation of land and the enlargement of leasing and land tenure, these were largely ignored and in 1838 the ‘Act for the Relief of the Destitute Poor‘ established the workhouse system in Ireland. Based on the existing scheme in England, the system divided the country into Unions in which a principal market town served as the focus for surrounding parishes or townlands. Manorhamilton was selected as the location of a Union Workhouse to serve the townlands of Manorhamilton, Kiltyclogher, Lurganboy, Killaga, Drumkeenan, Killenumary, Dromahair, Rossinver and Innismagraph. The Union was set up in October 1839 and a workhouse was built on land to the east of the town between 1840 and 1842 by James Caldwell, under the direction of George Wilkinson, the architect employed by the Poor Law Commissioners. The cost of construction came to £5,372 plus fittings at £1,075. (Anon., Vol.1, p. 25).

The workhouse was constructed to a generic plan used throughout Ireland and was of medium size in relation to others around the country. There were four principal buildings in all; the workhouse, a two storey stone lodge, a small infirmary and a fever hospital. Two inner walls, about 3m tall, and some ancillary buildings connected to the main buildings, formed an enclosed unit. The grounds were skirted by a gravelled avenue on the east side, circumscribing the lodge as far as a large yard at the rear of the workhouse and fronting the infirmary. This was the route of most activity such as the delivery of supplies and services. Accommodation for men was in the east wing while women and children were in the west. The wings were divided by a central section occupied by the Master’s Quarters, kitchens, store rooms and laundries. A small chapel stood to the rear.

Workhouse administration

The minutes of the Union Boards of Guardians survive and are kept in Ballinamore County Library (Anon., Vol.’s 1 & 3). These are detailed for the first few years but from the 1850s revert to a form recording only financial ingoings and outgoings. Both the finished copy of the minutes and the more detailed rough minutes survive, providing an insight into the early days of the workhouse, including the Famine years.

The first paupers were admitted to the workhouse on the 22nd December 1842. They are recorded as follows (Anon., Vol.1, p.99):

Pat Cullen aged 40

Hugh O’ Donnell aged 20

Mary Hart aged 40

Mary Plunkett aged 50

Peggy Hyhan aged 80

Ned Mitema (?) aged 80

It is worth noting that the ages are all rounded to the nearest decade, implying that these ages were approximations, either because the paupers were not asked or did not know their ages.

A further six were admitted a week later, this time with more detail as to age and circumstance:

Mary Murray orphan aged 18

Maigh Murray orphan aged 10

Mary Dolan orphan aged 12

Biddy Coyle deserted by husband aged 38

Mary Coyle child aged 10

Anne Clany idiot aged 40

After this names are not recorded, simply admission figures. These are, however, a telling record in themselves, as they cross the Famine years. It should be mentioned that the workhouse was designed with a potential capacity of 500.

Dec 1842 7

1843 166

1844 151

1845 56

1846 380

1847 767

1848 119 (March and May only)

Diet within the workhouse

The workhouse minutes record faithfully the goods purchased on a weekly basis as well as the average cost of maintaining a pauper. For example, the average weekly cost of maintaining a pauper in the typical week ending 15th July 1843 was 10 ½ shillings (Anon., Vol. 1, p. 99). The total week’s provision was as follows:

20 lb Bread 1 ½ lb candles

1600 lb potatoes 7 lb soap

112 lb meal 1 pair brogues

230 quarts buttermilk Mending 2 pair

150 quarts sweetmilk 2 bolts tape

2 mousetraps

Breakfast in the early years comprised 7 oz of oatmeal made into stirabout and either 1½ pints of fresh milk or 1 pint of buttermilk. Dinner was 3½ lbs of boiled potatoes and there was no evening meal. Meat was rare in the workhouse being served only on special occasions, such as Easter 1844, when 100 lbs of pork were delivered.

The diet was strictly enforced. In June 1843 (Anon., Vol.1, p. 183), a proposal to give women and girls employed in hard labour an additional 6 oz of bread and a half pint of milk per day was turned down. The reason stated was that ‘experience has shown that discipline can be better maintained in a workhouse without the addition of extra diet to particular paupers than with such allowances ….. any departure from (the ordinary diet) will become the cause of jealousy, discontent and insubordination.’ Adjustments were made to the dietary requirements of the inmates in some other circumstances. In March 1843 a meal of 1½ lbs of potatoes (weighed raw) and half a pint of buttermilk was substituted for the 6 oz of bread and half pint of new milk for children between 9 and 14, as this was thought to be beneficial. There is little evidence of green vegetables or fruit in the diets although it is not clear whether any food was grown within the workhouse itself. Potatoes were supplanted almost entirely by imported Indian Meal in the course of the 1840s as the effects of the potato blight were felt.

Education

After 1843, when the number of children in the workhouse was over 20, a schoolmaster and schoolmistress were appointed. John Moore was proposed and appointed schoolmaster at a wage of £15 a year and Mary Ramsay was appointed as his assistant (Anon, Vol.1, p. 294).

Health

Before the workhouse was opened, vaccinating officers were appointed to work within the Union, one at Manorhamilton, one at Dromahaire and one at Drumkeerin. A medical officer, Dr. Davis, reported weekly to the Board and in 1848, due to the high incidence of disease and illness in the Famine years, he was joined by Dr. Tate. Initially, some causes of death were recorded in the minute books but in general there are few instances of this. A John Green is recorded as dying of old age and debility at the age of 104 in March 1844 but perhaps his exceptional longevity was thought worthy of note in itself (Anon., Vol. 1, p. 338).

During the Famine years the workhouse was severely struck by a disease referred to only as ‘fever’. This was by far the greatest cause of famine related death recorded in all four provinces between the years 1846 and 1851 (Ó Gráda 1999, 89) although dysentery, diarrhea and dropsy were also recorded as major causes of death. According to O’Grada (1999, 88) ‘fever’ is likely to have included typhus, relapsing fever and typhoid fever. The disease is referred to throughout the Famine years when the hopeless overcrowding doubtless allowed it to spread rapidly. In May of 1848, it was reported that there was no decrease in the incidence of fever, with the total number of cases standing at 193; the medical officer reporting this died himself of the disease that year (Anon., Vol. 2, P. 69).

However virulent, the disease was not the deadly cholera, but there was considerable speculation about the possibility of its arrival. In January 1848, the central Board of Health requested to be informed what measures had been taken to provide prompt medical relief in the event of the disease making its appearance in the district. It was resolved that, in this event, a house at Donaghmore – then being used as an auxiliary workhouse – should be converted to a place for the receptions of cholera patients. The medical officer was expected to provide a list of medicines and medical ‘appliances’ necessary for the treatment of the disease. As a response, in May of the same year, tenders were put out for the construction of a fever hospital. A Mr Moore was accepted as builder in January of the following year with the lowest tender of £849. In the event cholera did not occur. The fever hospital is the one building remaining from the workhouse complex, standing to the north of the excavated archaeological site, and is currently in use by the North Western Health board.

Burial

There is little direct evidence in the minute books for burials or the location of the burial ground. The first reference to a graveyard is in 1844 when, following the death of an unnamed pauper, it was ordered ‘that a coffin be provided at the expense of the union at large and that he be buried in the ground lately set apart as a cemetery in the workhouse plot.’ Coffins appeared regularly on the list of purchases and this continued well into the Famine years, often at a rate representing extraordinarily high numbers of deaths. On 11th May 1848, twenty nine large coffins, four ‘second’ (i.e. smaller) coffins and four small coffins, were ordered. The following week, a further 12 large and six small coffins were procured. In July of that year 33 deaths were recorded. In June 1848, Lord Leitrim was requested to ‘grant a further space of one rood, five perches to enlarge the workhouse cemetery (Anon., Vol. 2, p. 91).’ Given the year, it is likely that this refers to the existing Famine graveyard to the rear of the workhouse curtilage.

Skeleton 9 Manorhamilton Workhouse

Archaeological excavation

Manorhamilton Workhouse was demolished in 1954 to make room for the current hospital. The only building to survive was the small fever hospital built in 1848 to cope with the feared outbreak of cholera. In 2001 construction works for a new North Western Health Board headquarters in front of this building revealed three coffined inhumations (Moore and Rogers 2002). Subsequent archaeological testing carried out by Declan Moore, revealed more burials in two areas, either side of the fever hospital, and it became clear that the former workhouse cemetery had been disturbed. Given the advanced nature of construction works, it was agreed that a 6m wide strip in front of the building, beneath part of the former car park surrounding this building, should be archaeologically excavated. Sixty six individuals were excavated in the summer of 2001 and a further seven in October of the following year due to a slight expansion of the construction works (Rogers 2002).

The graves were orientated approximately east-west and were concentrated in two areas, either side of the fever hospital. In the smaller area to the east (area A), there were two distinct phases but the graves were fairly randomly placed; whereas in the larger area to the west (area B), there were distinct rows. The graves were cut into a heavy green clay subsoil and the grave cuts were often difficult to distinguish, the redeposited clay only varying from the undisturbed natural subsoil by the inclusion of occasional burnt stones or shells. Where they were identified, the cuts were generally fairly tight to the coffin, in cases even ‘shouldered’ to follow the shape of the coffin. The tops of the coffins were generally about 500mm below the tarmac surface although it was clear from overlying deposits of mixed modern material, probably dating from the demolition of the workhouse, that there had been considerable disturbance in this area and this is probably not an accurate record of their original depth.

Orientation of the burials was surprisingly variable. The standard assumed Christian burial is that of west/east, with the head to the west, so that on the day of the resurrection an individual would face Jerusalem. At least 13 individuals, all in area B, were laid with heads to the east. The significance of this is unknown at present.

The burials

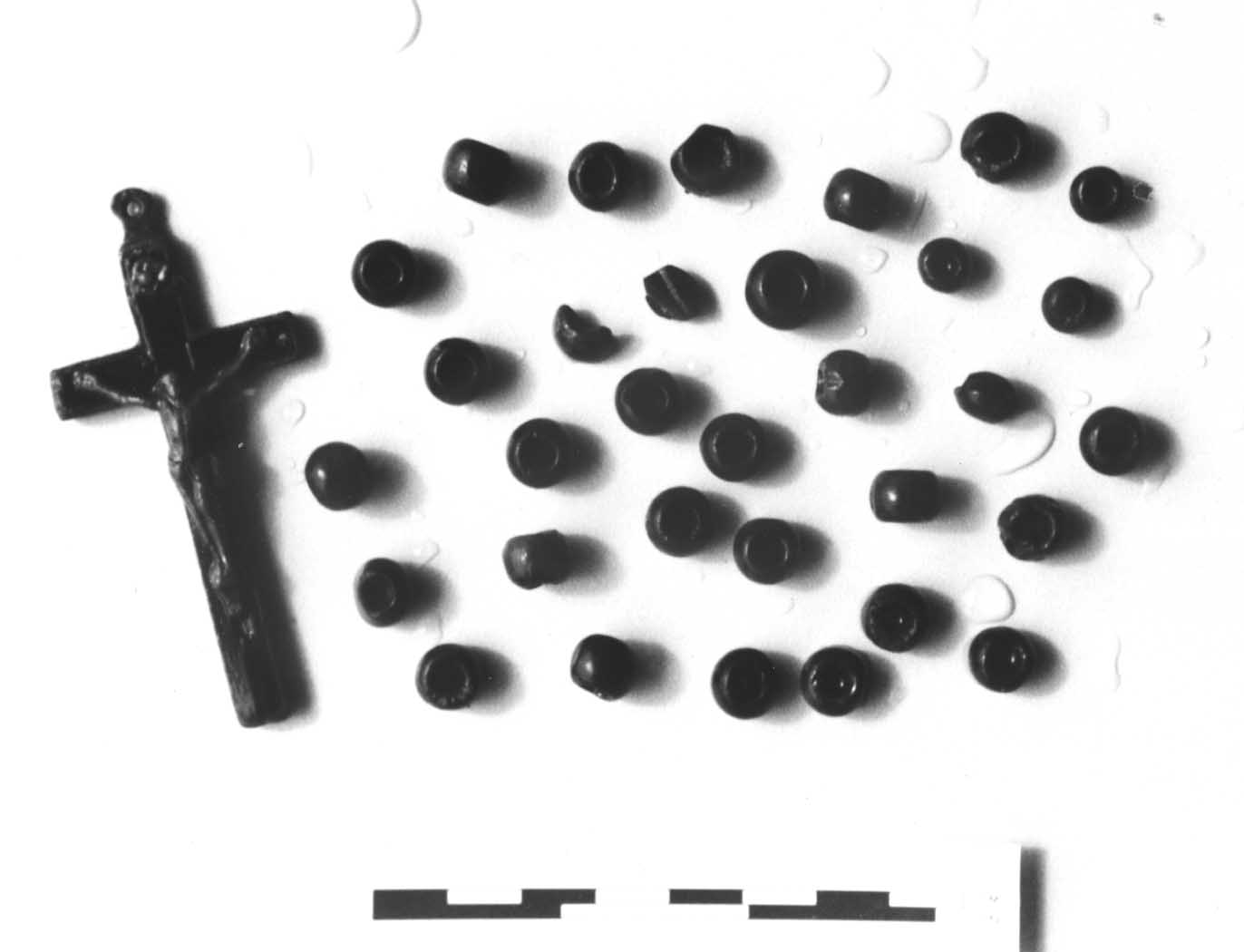

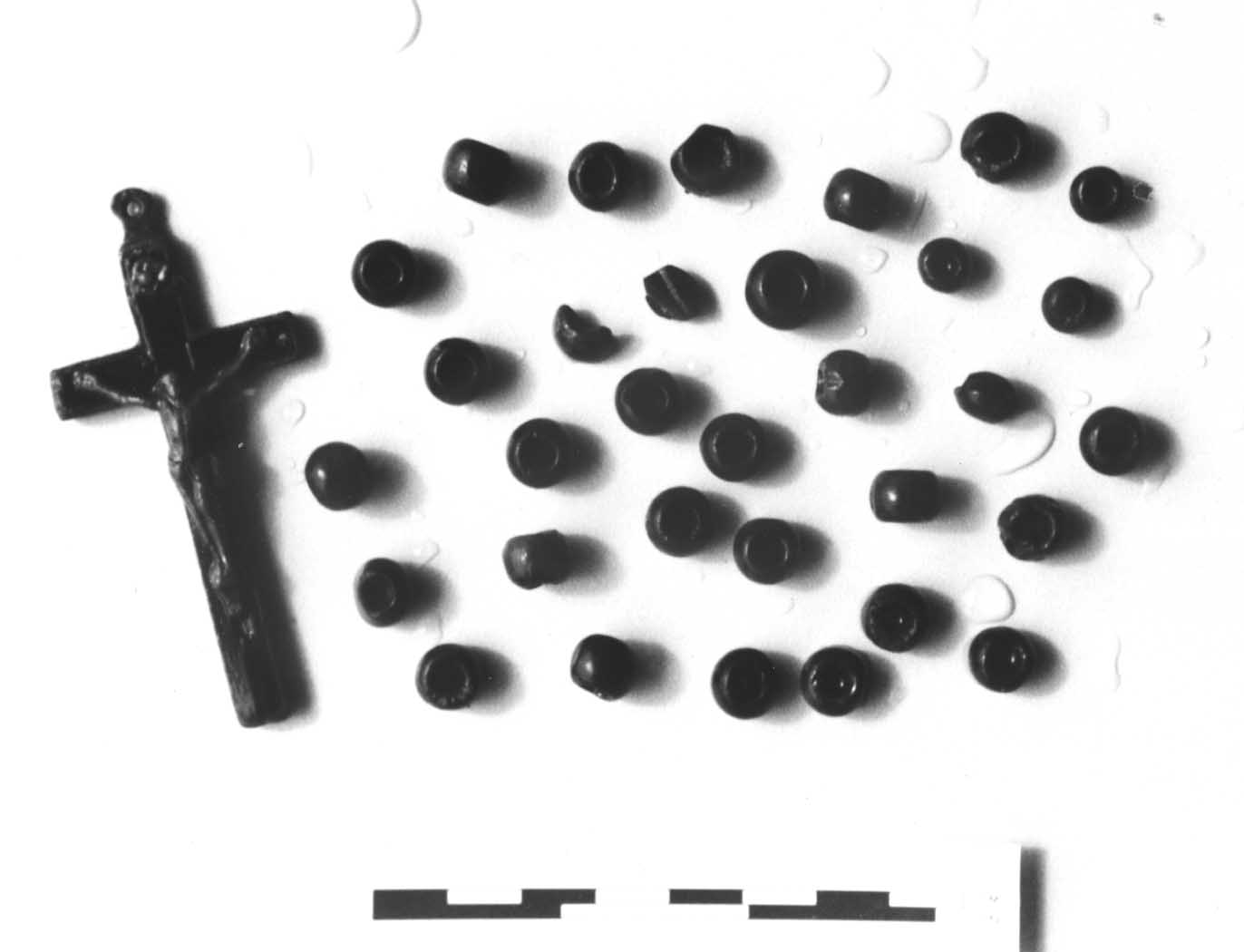

Preservation of skeletal remains varied widely across the site dependent on the differing amounts of water in the soil. To the west of the site, some skeletons were in an excellent state of preservation, while to the east, one coffin contained only five teeth. Pockets of water trapped in the clay would have been detrimental to bone preservation. Surviving skeletons were supine with arms generally laid by the sides. Textiles were found in several of the coffins, presumably the shrouding material described in the minutes of the Boards of Guardians (Anon, Vol. 2, p. 80). Rosary beads were found with three of the skeletons. Skeleton C109 had 11 wooden beads, a crucifix and a heart shaped medallion underneath the cranium, while C259 had a simple set of wooden beads around the neck. Skeleton C317 had eight glass beads and a crucifix of copper alloy at the left shoulder.

Preservation of the coffins varied but generally it was very good. The clay was waterlogged and the anaerobic conditions would have aided the preservation of wood. The coffins were solidly constructed, joined with nails and, in two cases, double layered at the sides. They were simple, with no ornamentation, handles grips or any other kind of decoration being found. Organic matter, almost certainly straw, was found lining the bases of three of the coffins. Most coffin lids had split and collapsed inwards with the weight of the overlying grave earth. Wood analysis from a sample of coffins from both sites showed the wood to be spruce (picea), probably from a managed, fast growing plantation (Stuijts, 2003).

Skeletal remains

Osteological analysis of the first phase of excavated skeletons was undertaken by Linda G. Lynch. The individuals buried in a Union workhouse cemetery comprise a very significant bias in a skeletal population. They cannot be said to represent the whole population of a specific period, but rather of those select individuals who were actually admitted to a workhouse (Lynch 2002). Even this latter sample may be biased. As Guinnane and Ó Gráda observed (2000, 2) ‘a workhouse in which everybody died shortly after admittance might seem badly managed, but this is not a sound conclusion if this workhouse only attracted those in the most extreme state of need. Similarly, a workhouse where everyone lived might seem well-run, but it could also be one in which the master refused admittance to anyone who might actually need assistance’.

A total of sixty-six skeletons were recovered from Manorhamilton from sixty-one individual graves. in phase one of the excavation. There were forty-seven adults (twenty-seven females, nineteen males, one sex undetermined). There is a probable bias in the adult population towards females. Females were more frequently admitted to workhouses than males, as they were more vulnerable as a result of death, desertion, and emigration of spouses, than their male counterparts (O’Mahony 2005, 50). In Cork Union Workhouse in August of 1846 records show that 74% of the inmates over 15 years of age were female (O’Mahony 2005, 41). Unfortunately, poor rates of preservation significantly hampered the age-at-death assessment of the adults. Of the nineteen juveniles, there was a predominance of individuals aged between 5 years and 15 years at the time of death. High levels of dental caries and calculus are comparable with modern day trends, and also of the diet of the period and indeed that prescribed in the workhouse. In addition many individuals may have used their teeth as tools of their occupations, and a high number of male adults had dental lesions indicative of pipe-smoking. There was significant skeletal evidence of nutritional deficiencies, certainly from early childhood. Degenerative joint disease was common, and there were clear variations in both severity and frequency between the age groups and sexes. Non-specific infection was also present in this population, in addition to infections occurring secondary to trauma. A number of specific infections were identified including sinusitis and middle-ear infection. Metabolic diseases in this population included iron deficiency, vitamin D deficiency, and internal frontal hyperostosis. The latter manifests as thickened bone growth on the internal surface of the frontal bone of the skull. It has been linked with changes in the pituitary hormones after menopause and has a much higher incidence in females (Ortner and Putschar 1981, 294).

Crucifix and rosary beads found with skeleton c109

Osteological findings from the Manorhamilton burials generally were indicative of the poor socio-economic background and physical hardship of the inhabitants of the workhouse and is in stark contrast to another probably contemporary population studied by Lynch from a Church of Ireland cemetery in Sligo town, in use from the late 18th century up until the early 20th century (Lynch 2001). Some similarities were observed between the populations, such as low rates of dental attrition, a phenomenon that is also common in present-day Irish populations. However, there are some significant differences between the two 19th century populations. Numerous individuals from Sligo, for example, displayed evidence of access to advanced systems of medical and dental care, and all indications are that the population were of quite high socio-economic standing. In comparison, the individuals from Manorhamilton would have consisted primarily of the lowest socio-economic classes, with many paupers, and this is clearly reflected in the skeletal remains.

Some of the adults exhibited lesions which are suggestive of time in a nursing institute rather than a classic workhouse. These include one individual with severe and multiple, but partially healed, trauma to the bones of the thorax, another who would have suffered from motor and sensory problems resulting from a broken neck. Yet another individual with a badly broken leg resulting in severe infection, and there was one child with a serious but unidentified systemic infection. These would all have required a significant amount of care that may not have been available in the earlier version of the workhouse system. It is also possible these individuals may have been viewed as too great a burden on a community and may have been admitted to the workhouse as a way of dealing with the problem.

The individuals buried here were under considerable physiological stresses, some evidently since early childhood. The situation as regards the juveniles may have been slightly different. In general, there is little evidence of disease processes amongst the skeletons of the juveniles suggesting that they may have succumbed relatively quickly to whatever they died from. In addition, the double and triple burials of children suggest that they may have been dying in high numbers, during some period of use of the cemetery.

Medallions found with burials at Manorhamilton

Date of the excavated skeletons

Reburial of the remains of these individuals occasioned further ground testing and this confirmed that burials extend at least 6m northwards from the excavated areas (Rogers, 2003). Thus, there may be many hundreds of skeletons beneath the car park of the present St Joseph’s building. It is known that the first graveyard was full by 1848 and it is therefore likely the remains described were buried in the years between 1842 and 1848.

For more on the Great Famine see this post.

More tomorrow – Creagh Junction, Ballinasloe and the Connaught Asylum….

This entry was posted on Tuesday, October 21st, 2008 at 10:39 am. It is filed under About Archaeology, Papers & Reports and tagged with Archaeological Services Galway, Leitrim, manorhamilton, osteoarchaeology, paleopathology, skeletons, workhouse.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.