Not the Large Hadron Collider, just a wheel

Here’s object number two in our virtual museum – a late medieval wheel from Galway City. As with the palstave, we’ve also presented a brief report on the find including a description of the circumstances of its finding.

Although it’s a somewhat less spectacular object, it’s one of those rare pieces which reflect everyday life in late medieval Galway, and as such has its own poignant significance.

As part of the Eyre Square Enhancement Project (Moore Group was engaged by Galway City Council as the consulting archaeologist on the project) the northern carriageway, including the old taxi rank, car park and casual trading area, was monitored and/or tested in advance by Billy Quinn of Moore Group.

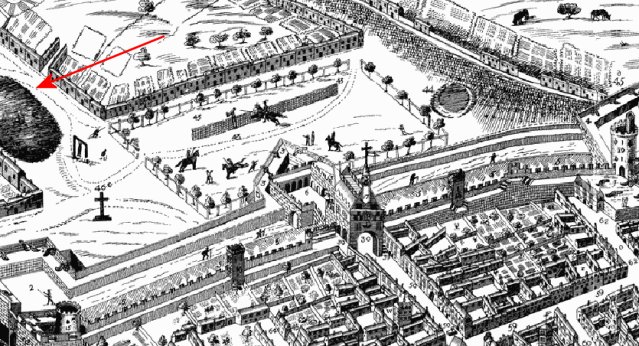

The most significant discovery during the course of the excavations in this area was a peat deposit with obvious high archaeological potential. This feature is represented on the Pictorial Map of 1651 as a catchment area for water that developed into a ‘pool’ or ‘quagmire’ and was known by archaeologists to still be present in the area under the existing surface. The peat deposit had been cut by various service lines down through the years but remained largely intact. This peat deposit was found throughout the north of the square but was most evident towards the east in an area between Nos. 41-42 Eyre Square (Galway Advertiser office) and the old taxi rank.

Detail of 1651 pictorial map showing location of the 'pool'

Pre-development testing in advance of construction works had highlighted its existence and prior to the installation of a new 225mm diameter storm drain service trench a decision was made in consultation with the relevant people to preserve the layer in situ as much as possible. Permission was granted to mechanically excavate the trench but as a remedial measure, to prevent slippage and ensure minimum impact, the base and sides were covered in terram and backfilled immediately.

Discovery

The excavated fill was monitored and subsequently sifted through for finds and subsequently metal detected. The peat varied in depth from 1m to 2.5m and contained organic debris, animal bone, shell, leather fragments (including shoe soles) and sherds of post-medieval and medieval pottery. Metal detecting through the spoil was rewarded with the recovery of a small strand of gold gilt wire. This wire was probably intended for filigree ornamentation involving openwork of delicate or intricate design, a jewellery style popular in the late Nineteenth century.

A more pedestrian find but of equal note was that of a block carved wooden wheel and axle found within the peat near the western terminal of the old bus stop area. The wheel was found while digging a drain for a new gully.

Find Location

Description

The wheel was carved from a single block of timber and measures 370mm in diameter by 73mm thick and could have been used for a cart or barrow. The wheel has a square section wooden axle through it, with ferrous dowels protruding from the centre at each end. The axle measures 72mm in diameter by 255mm long. Close to the wheel there are wooden dowels. There also appears to be the remains of roping around one end of the axle. Some tool marks are visible.

Wheel post conservation

Condition

The wood is in very good condition and the wheel is complete with some minor superficial dirt. Some concretions have formed on the axle terminals and on the iron dowels.

Treatment

A gentle clean using fresh water was carried out by Arch-Con Labs in Dublin, followed by the impregnation of the wood with polyethylene glycols for 10 months, followed by freeze drying. Some minor surface treatment was carried out.

tool marks visibly on upper surface

Conclusion

The Eyre Square enhancement scheme afforded us a unique, albeit keyhole, view of Galway’s late medieval – post medieval past. Given the practical constraints of development (not to mind the need for the City to continue functioning) a full archaeological excavation of the subject area was not feasible. Rather, archaeological mitigation involved the undertaking of an initial phase of targeted testing followed by archaeological monitoring, and where necessary excavation, to record finds, features and materials of significance as they were encountered during the course of the groundworks. As with any proposed development within an urban context and particularly one as central as Eyre Square the possibility of uncovering in situ archaeological deposits is of course relative to the degree of ground disturbance over time. In Eyre Square these impacts were considerable. Although the basic arrangement of the park and surrounding streets is recognizable from the 1651 map onwards, the actual topography of the area has changed significantly due to general re-development works involving ground reduction, infilling, road widening, resurfacings and the installation of an assortment of subterranean services.

Detail showing wooden dowel

Notwithstanding these incremental changes it was surprising how much archaeological material survived undisturbed. To the north of the square, excavations located the foundations of an eighteenth century market house (see here) which was exposed, recorded and retained in situ. The excavation of a trial pit to the north east of the market house also exposed an interesting stratigraphy of successive levels of the old road surface. These metalled layers marked the location of the market area leading east towards Prospect hill and beyond.

Whether the wheel was deliberately dumped in ‘the pool’ is impossible to determine. Although some may see it as a mundane and simple object, and perhaps it doesn’t have the immediate appeal or impact of, say, an Ardagh chalice, much of our archaeological heritage is similarly unspectacular or is invisible. Archaeology has been described as ‘the study of durable rubbish’ (to paraphrase Edwards & Anderson) and the wheel is one of those mute objects which doesn’t speak to us about the great and the good of the period. Nor does it tell us anything of the great upheavals of the time. Rather, it reflects the weary monotony of the workplace. Who knows? – perhaps its a long lost fragment of an Eyre Square traders barrow, or that of a tradesman or a fishmonger, discarded after the barrow finally fell apart, only to be found again several hundred years later, treated with polyethylene glycols, freeze dried and put on the internet!

Most of the time archaeologists must be content with merely helping to fill out the picture of the social world or daily life of the area in which they work and the wheel is just that – an unspectacular object demonstrating evidence of how people lived and the simple objects they used in late Medieval Galway.

The works at Eyre Square were financed by Galway City Council.

Bibliography

Hollund, H & Bernaciak, K., 2008 Artefact Conservation Record C07-0014, Arch Con Labs Ltd.

Edwards, B. & Anderson, C., 2004. Through the British Museum with the Bible. Day One.

This entry was posted on Wednesday, September 10th, 2008 at 1:49 pm. It is filed under About Archaeology, Papers & Reports, Virtual Museum and tagged with 1651 pictorial map, environmental consultants galway, Eyre Square, galway, large hadron collider, moore archaeology, quagmire, wheel.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

I almost wept. Almost. 😉

Hey i am just wondering on that map there are three crest in the top right hand corner i wonder dose anyone know what family they belong too