On April 6th 1916, barely three weeks before the Easter Rising, Paddy Maher (a 35 year old British Army veteran who had seen service in China and Gallipoli) from Lower Conaghy, County Kilkenny, had just arrived at the Front. The Battalion had shipped into France from Egypt in March as part of the latest push against the German Army on the Somme. After three days in the mud, a massive German bombardment began. In a period of just one hour, over 8000 howitzer and mortar shells rained in on Paddy’s stretch of trench. The following day Paddy and 12 others in Mary Redan (a salient) were recorded missing, their bodies buried in the collapsed trenches in the fields of Northern France.

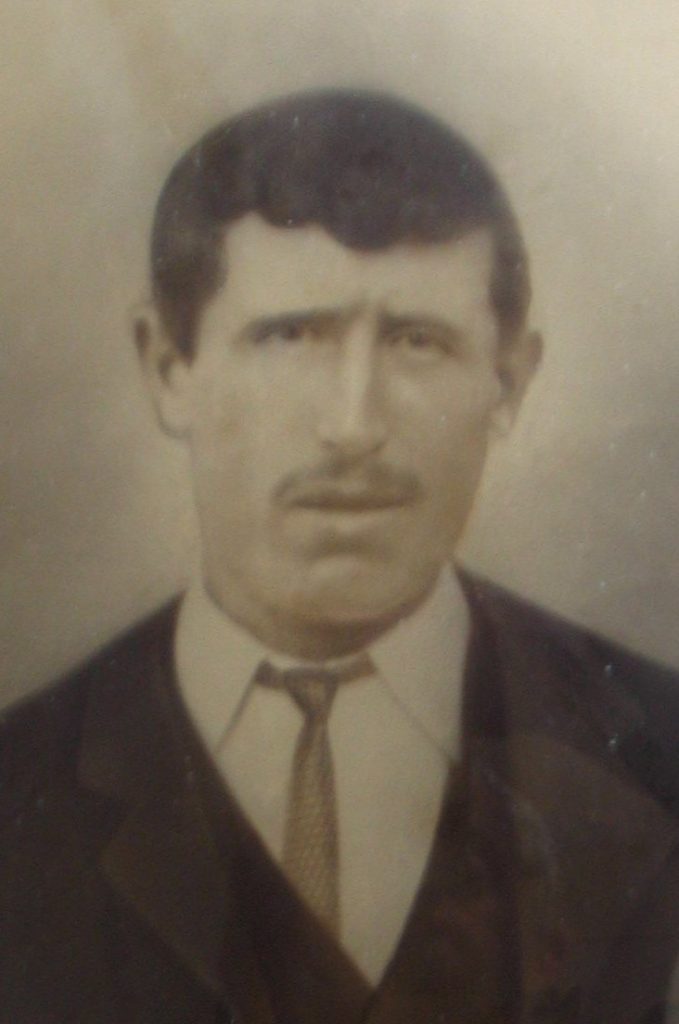

Pictured above: Paddy Maher

Ralph J. Whitehead describes in detail the events of that night in his book ‘The other side of the wire’ (2010), excerpted below;

On the night of 6/7 April RIR {Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment} 119 sent out four patrols from the II Battalion against Mary Redan in sector 47…. The raiding party consisted of three officers and 78 other ranks….

1. Coy, 2nd South Wales Borderers occupied Mary Redan on the night… It was their first time in the trenches and they had only been in the line for the past three days. It was to be an experience the men would not soon forget…. The preliminary bombardment was very effective as entire sections of wire entanglements were destroyed, dugouts were smashed in, telephone lines were cut and much of the front line trench was blown in….

Three patrols moved into the British trenches as planned while the fourth remained to the rear as protection and to supply support as needed. The raid lasted no more than 15 minutes and the result was the capture of 19 prisoners from the 2nd South Wales Borderers who became trapped inside a dug-out due to the intense bombardment.

At 10.30 p.m. the bombardment suddenly ceased and the Battalion could reoccupy the front trench and set about investigating and repairing the damage. This had been considerable. It was ‘a terrible shambles’, one officer writes, ‘bay after bay being blown in and killed and wounded being buried under the blown in trenches.’ Not only the front line but the communication trenches were badly knocked about, the wire had practically been completely demolished…. The bombardment of the British lines completely smashed the front line trenches… The total casualties suffered by the 29th Division amounted to 112 officers and men; one officer, 33 other ranks killed….

Jack Sheldon’s ‘The German Army on the Somme’ (2005) also describes the raid. He notes that it was led by Leutnants Kaiser, Burger and Sternfeld, was well planned and executed.

The War Diary for the day also describes the event (lifted from this blog post relating to the death of Private Edmund David Cook who also died on the day and who probably served alongside Paddy Maher throughout the war):

‘The 4th and 5th April were without incident but on 6th April at about 9pm, a very heavy bombardment was opened by the enemy. This bombardment was concentrated on the right half of ‘C’ Company commanded by Capt F.S. Blake, on communication trenches leading up to it and on the portion of trench further north from which the front of ‘C’ Company’s trench could be enfilladed. The bombardment lasted until 10.30 pm when it ceased as suddenly as it had begun. It is not an exaggeration to say that the bursting of shells was so frequent that the communication trench from Bn H.Q towards the front line was lit up continuously. The trench held by the right half of ‘C’ Company was demolished…’

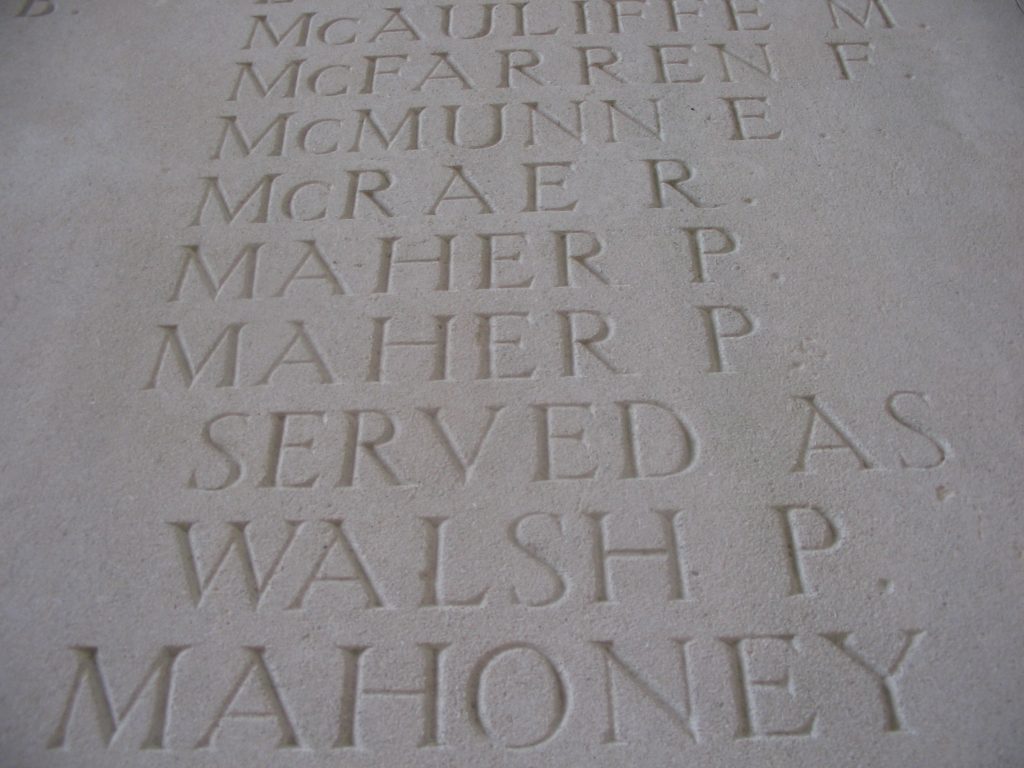

Paddy’s body was never recovered. He is recorded in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission files as Patrick Maher (Served as WALSH), Son of James and Mary Maher (nee Walsh), and both his real and enlistment name are inscribed on Pier and Face 4 A of the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (over 72,000 missing). He was awarded the Victory and 1914-15 Star medals for his service.

Patrick Maher on the Thiepval Memorial

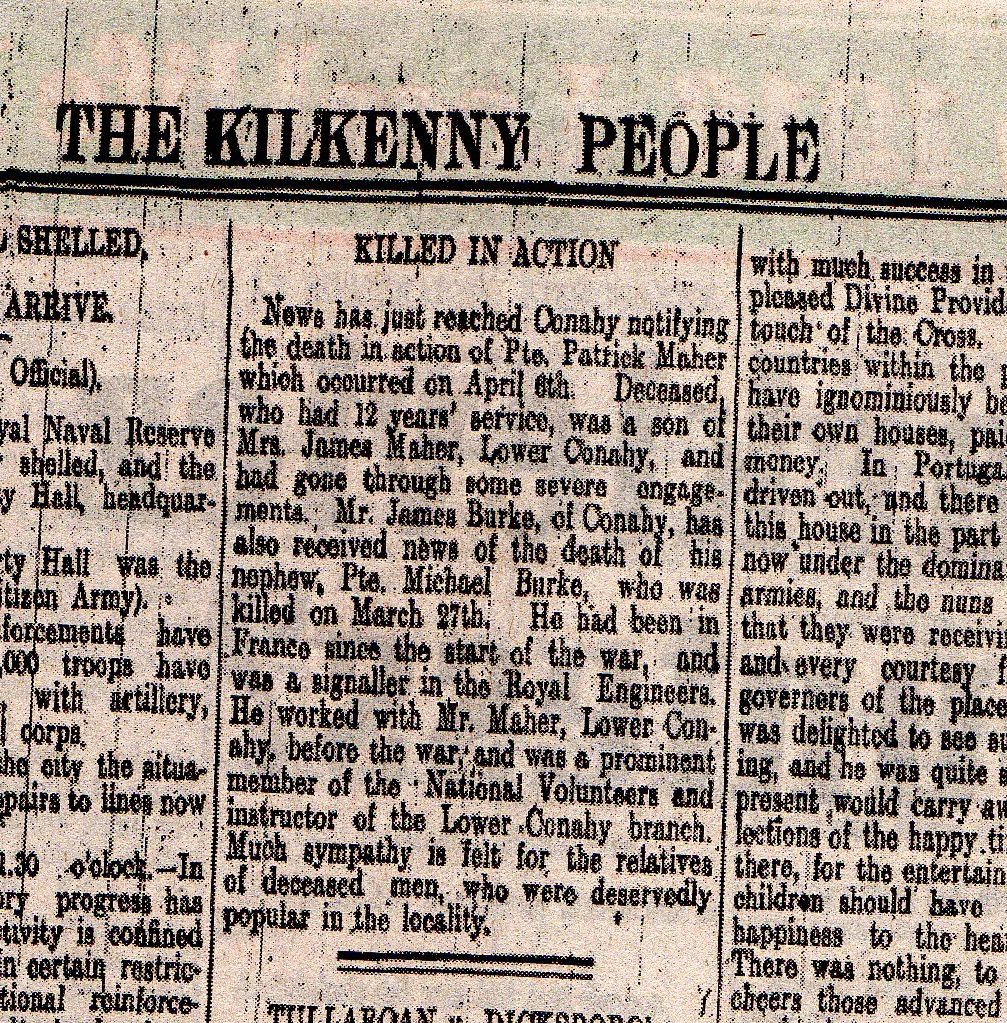

His death was reported in the Kilkenny People on Saturday April 29.

Killed in Action

News has just reached Conaghy notifying the death in action of Pte. Patrick Maher which occurred on April 6th. Deceased, who had 12 years service, was a son of Mrs. James Maher, Lower Conaghy, and had gone through some severe engagements. Mr. James Burke of Conaghy, has also received news of the death of his nephew, Pte. Michael Burke, who was killed on March 27th. He had been in France since the start of the war, and was a signaller in the Royal Engineers. He worked with Mr. Maher, Lower Conaghy, before the war and was a prominent member of the National Volunteers and instructor of the Lower Conaghy branch. Much sympathy is felt for the relatives of deceased men who were deservedly popular in the locality.

Paddy Maher was my mother’s uncle, my granduncle. Since learning of his existence 8-9 years ago I’ve been researching his service record and motives. Why he enlisted under his mother’s maiden name is unclear, but it may have something to do with the activities of his brothers and their involvement in the fight for Irish Freedom (see footnote), but I’m uncertain of their activities in that regard in the first decade of the 20th century. He enlisted in Cardiff in 1904. By 1910 the 2nd Battalion, South Wales Borderers (SWB), were stationed in post Boer War South Africa. The Battalion was sent to the Far East in 1912, so at the outbreak of the war Paddy is likely to have been at Tientsin in northern China. In September 1914 the Borderers were sent to Lao Shan Bay for operations alongside Japanese troops against the German territory of Tsingtao. The German garrison held out for nearly two months despite being outnumbered 6 to 1 and subjected to heavy, sustained bombardment.

By January 1915 the 2nd SWB were back in Britain training for France where they came under orders of the 87th Brigade, 29th Division before embarking at Avonmouth for Gallipoli on St. Patricks Day, 1915.

On the 25th of April 1915 they landed on S beach at Cape Helles. Unlike other landings the Borderers succeeded in reaching their objectives relatively unscathed. They would, however, be among the last to leave the Gallipoli campaign in January 1916. The 29th Division took part in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battles of Krithia before moving to Suvla Bay where they were deployed in the Battle of Scimitar Hill. Paddy’s C Coy served as the frontline alongside D Coy on the charge against Hill 70 on August 21 1915, which, despite dense fog, they succeeded in capturing. They were forced to withdraw in the evening suffering the loss of one third of their men. Casualty figures for the Gallipoli campaign vary, but it is likely that over 100,000 men were killed.

On 11th January 1916 the Borderers moved to Egypt and went on to France, arriving at Marseilles on 15th March 1916 and on to the Somme.

On a very wet and dreary day with rolling, angry clouds overhead in mid-March 2008 I visited the location of Mary Redan. Clearly visible in aerial photographs as a chalky cropmark, it sits at the top of a low ridge.

It’s roughly 500m east of the Newfoundland Memorial Park and north west of the Ancre British cemetery in Auchonvilliers (rendered ‘Ocean Villas’ by the British troops) in Picardy. The Park presents a largely preserved section of battlefield along with memorials to the 51st (Highland) Division and the Newfoundland Regiment which suffered great losses on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme later in July 1916.

Pictured: Caribou Memorial to the Newfoundlanders

Mary Redan is accessed via a field to the east of the Park, which in March 2008 had been recently ploughed and was heavy underfoot. In wet weather the churned-up soil turns to a gluey chalk-patched loam, a spongy mess. The soil at the site of the trench is a reddish brown with lumps of chalk indicating where the ground had been disturbed.

All around there are chalky patterns in the clay indicating the locations of other trenches or shell crater sites. My muddy shoes collected a harvest of shrapnel, a cap badge and spent bullet shells. Activities such as ploughing still turn up shells and other ordnance in the area. Farmers often pile these shells in farmyards or the side of fields awaiting collection by the French or Belgian armies – it’s known as the ‘Iron Harvest’.

The surrounding landscape is undulating and today is mainly unenclosed arable fields with occasional small stands of woodland, military graveyards and memorials. The site of Paddy’s trench is now a pleasant open vista of greens and yellows towards the east, as opposed to the pock marked, cratered, brown and grey sea of mud he must have witnessed. It’s hard to look over today’s pastoral landscape and picture the mudscape of 1916 and impossible to imagine the horror of that bombardment in April 1916.

Of the three Irish divisions numbering 210,000 Irishmen (most of them volunteers) who fought with the British Army in World War I it is estimated that over 35,000 died. Thousands of other Irishmen such as Paddy fought with other British units and in the forces raised by the overseas dominions of the British Empire.

As to Paddy’s motives we can only speculate as no family knowledge of his reasons for enlistment have been passed down. Irishmen enlisted for a variety of reasons; some in defence of small nations, others for more local considerations. Many nationalists were persuaded to join up by John Redmond with the promise of an Irish ‘home rule’ parliament in Dublin. Paddy was the eldest of the family and enlisted well before the First World War so maybe none of these motives apply – perhaps he simply didn’t fancy life on a small Kilkenny farm.

Footnote

‘If these men must die, would it not be better to die in their own country fighting for the freedom of their class, and for the abolition of war, than to go forth to strange countries and die slaughtering and slaughtered by their brothers that tyrants and profiteers might live?‘ (James Connolly, 15 August 1914).

The same issue of the Kilkenny People mentioned above headlined the ‘Terrible Scenes in the Capital’ as the Easter Rising erupted. Rumour had reached Kilkenny early on the Monday that the Irish Volunteers had rebelled and practically occupied Dublin City.

That week James Connolly’s words must have held special resonance to Paddy’s brothers, Nicholas and Edward Maher, as they mobilised with the Irish Volunteers in Kilkenny City. My Grandfather, Michael Maher and another brother, Jimmy, may have been persuaded to stay home at the farm in Conaghy with their mother and four sisters (although Michael later served during the War of Independence). Perhaps she didn’t want to run the risk of losing all her sons in the same month.

Nicholas, Captain of the Conaghy Company, and Eddie mobilised on Easter Sunday. Tom Treacy dismissed the men and ordered them to return and form up again on Easter Monday. They mustered throughout the week, but news of the surrender in Dublin arrived on Easter Saturday and all their weapons were stowed away and the volunteers were sent home. Nicky and Eddie appear to have then gone into hiding or gone on the run for some time after. Later, they served in the War of Independence alongside my Great Grandfather and my Grandfather, who were later interned in the Curragh during the Civil War (where they escaped alongside a large group of IRA men through a tunnel they had assisted in digging, for a time). But that’s another story altogether.

Bibliography:

Sheldon, J., (2005). The German Army on the Somme 1914 – 1916. Pen and Swords, England.

Whitehead, R.J., (2010). Other Side of the Wire Volume 1: With the German XIV Reserve Corps on the Somme, September 1914-June 1916. Helion and Company, England.

Other sources:

http://www.cwgc.org/

http://coastwallker2.blogspot.ie/2016/04/edmund-david-cook-edmund-davidcook-is.html#comment-form/

The British National Archives , Kew, Surrey, UK

Kilkenny People, Kilkenny

Post Script: I wasn’t going to post this publicly – this was originally intended for family and friends only, but in the course of researching the post I came across the blog post about Pte Cook and decided to share the post as a result. Maybe relatives of the other men of Mary Redan will be interested and can add to the story. Feel free to correct any of the information in the comments section.